METABOLIC TESTING: AVOID THE BONK

METABOLIC TESTING AND THE BONK

As many of you know, I spend a few hours every day getting to interact with retail customers at the Playtri Store. It’s a great experience for me as a coach, because I get to hear and consider all the questions that athletes have regarding the sport. It often leads to quality conversations that hopefully have a positive impact on the athlete’s training and racing.

A common question prior to every big Ironman race is “I’m trying to figure out my nutrition – what should I do/use?” I always hope athletes are asking for a race months down the line, but more often than not, they’re asking for a race in a week or two.

First, know that nutrition is king in Ironman. It isn’t a last minute consideration. All the quality training in the world can fall apart in a blink on race day with the wrong nutrition strategy (I’m not even going to get into hydration here – see the last email article on hydration and electrolytes).

Let me explain. Athletes who have been training or racing long course have likely all experienced “the bonk” – that dreaded sensation of suddenly hitting a point where either the muscles stop firing, the brain stops thinking, or, you know, both. It will quite literally stop you in your tracks. It happens reasonably often in triathlon, and exponentially more at the Ironman distance. Note that bonking is NOT the same as cramping (another evil villain of endurance sports), though they can definitely happen concurrently!

Bonking occurs due to a lack of carbohydrates available to brain and/or muscles. Why does this happen? Without going too deep into the science, carbohydrates and fats are both potential energy sources for the creation of ATP (Adenosine Triphosphate), a chain of three molecules that split to create the energy that causes muscles to contract (allowing us to swim, bike, run, etc.). Of the two potential energy sources (fat and carbs), carbohydrates are easier for the body to access for the process of creating ATP, so the harder we work (swimming, biking or running faster/harder), the more our body moves towards relying on carbs instead of fat. This would be great, except that, while our bodies have massive stores of fat (that’s not a comment on the reader’s weight – even the leanest athlete has enough stored fat for days at any given time), our carbohydrate stores are much more limited – perhaps 500g (2000 kcals), give or take 100g.

This is where we run into a problem. Some athletes may burn through 1000 kcals or more of carbohydrates in an hour at high intensities, meaning they could easily burn through their stores before their event is completed (fun fact – the average Ironman finish time is 12:35:00 – significantly longer than 2 hours, which is approximately how fast you’ll burn through your carbs at 1000 kcals per hour). You likely have two questions for me now:

1. Can’t I just replace the carbs I’m burning? Isn’t that what gels are for?

Yes, thank goodness. The challenge is that, on average, women can only absorb 100-200 kcals of carbs an hour, and men can only absorb 200-300 kcals an hour, at moderate intensity (yes – the faster you go, the more carbs you burn, and the harder it is to absorb carbs that you are consuming!) So if you’re burning 1000 kcals of carbs an hour, and can only replace 200 kcals – you do the math, but you’re still not making it to 12 hours and 35 minutes before you bonk.

2. If I burn through all my carb stores, won’t my body just slow me down and start using fat stores instead?

Unfortunately it isn’t that simple – aerobic metabolism requires some carbohydrates, even at very low activity levels, so if the carb tank is empty, you’re probably not going anywhere, slow or otherwise.

3. But the pros are going super-fast – aren’t they burning through 1000’s of carbs on the bike?

Yes, the pros are going super-fast – but we have to remember that our super-fast is their moderate. It isn’t that their bodies just have more carbs to burn, they just maintain higher power/speed at lower heart rates.

Many athletes take the trial and error approach – while doing progressively longer workouts, they test different nutrition strategies and track successes and failures, hopefully narrowing it down to something that works. Of course, that means if you don’t have many successful experiments before race day, you may or may not have a solid plan going into your event. There’s definitely a “hope for the best” element to this strategy that isn’t my preference, but has certainly worked for plenty of athletes, so I won’t knock it.

However, at Playtri we utilize a form of performance testing that takes a good deal of the guesswork out of nutrition strategy for Ironman, which we call “Caloric Expenditure Testing,” or “Metabolic Testing.”

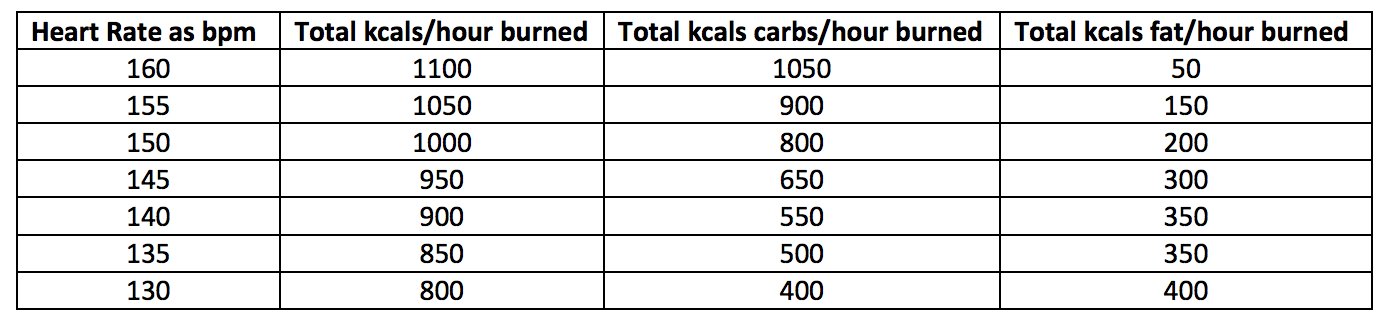

I just about require all of my 70.3 and IM clients to complete this 15-20 minute test, which gives me a data chart that looks something like this:

Athlete Name: Edna Example

Test Date: May, 2017

Test: Bike

Let’s say this chart was completed for the athlete on the bike. If the athlete wanted to do her IM bike in 6 hours, and could average 19 mph on the bike on race day at 130 bpm, she could take 100 kcals of carbs an hour and come off the with carb stores essentially intact. So let’s say she isn’t quite that strong, and her heart rate will be at 145 for her to maintain that pace – taking 100 kcals of carbs an hour would now mean that she burned through 900 kcals of carbs prior to starting the run. Well, if she had 2000 kcals in the tank to start, that means she may have 1100 left for her run (not counting kcals burned during the swim), which, if she has the same chart for her run calorie expenditure, it could then be determined if that was enough to achieve her goal for the day.

For many athletes, doing the test and understanding how much they burn at different heart rates is enough – they or their coach can take the information, and formulate effective plans for training and racing.

However, what if the chart looked like this:

Athlete Name: Edna Example

Test Date: May, 2017

Test: Bike

Even if the athlete can hold 19 mph at 130 bpm, and absorb 100 kcals of carbs an hour, she would still burn through 1800 kcals of carbs during the bike, leaving her with next to nothing to run her marathon on. Assuming she has done this test some months prior to her race, she has three options:

1. Change her goal (go slower than 6 hours on the bike)

2. Improve her ability to utilize fat instead of carbs at 130 bpm

3. Improve her power/speed at a lower HR

If she is doing the test a week before her race, she has one option:

1. Change her goal

This is why we recommend doing this test twice during long course training – once at the beginning of training to assess the situation, and help the athlete or coach effectively plan their focus for the coming training block (instead of just hoping for decent numbers prior to race day), and then once right before the race, to re-check numbers going into the event, and finalize the nutrition strategy.

Hopefully, this gets your gear spinning on long course nutrition. Of course, it isn’t just a numbers game. Other considerations, like what type of nutrition to take in, how to time it with hydration, what you personally are able to absorb, etc., are also part of the planning process. The most important thing is to start planning nutrition NOW, and make sure you have as much data as possible to do it efficiently. If you have questions, feel free to reach out to me, or any of the other Playtri coaches.

Learn more about Performance Testing at: playtri.com/testing/